Notes for Pages 120-129.

< 110-119 | Notes Index | 130-139 >

120. Lucien: god’s own drama queen. He could probably inject an air of poetic doom into ordering a stack of pancakes.

“Laid on the table†– the sacrificial table, that is. Like, you know. Aslan. Or Aztecs.

121. STUDYING MONTAGE! Suggested soundtrack: “Eye of the Tigerâ€.

The lecture hall has an interesting history and many variants, although today  there’s a great deal of consistency the world over. You can tell this one is pretty contemporary by the fact that the floor is raked, rather than flat, by the presence of the writing desks (note-taking was somewhat patchier in pre-modern times), and the fact that Luther is standing at a relatively simple lectern, rather than sitting in an elaborate, carved throne or a balcony of the sort you’d find in a monastery.

there’s a great deal of consistency the world over. You can tell this one is pretty contemporary by the fact that the floor is raked, rather than flat, by the presence of the writing desks (note-taking was somewhat patchier in pre-modern times), and the fact that Luther is standing at a relatively simple lectern, rather than sitting in an elaborate, carved throne or a balcony of the sort you’d find in a monastery.

Luther has a morning class, poor thing. I suppose every new lecturer must dread finding out they’ve been assigned an 8:30am slot, and sit there, gripping their coffee, frantically re-reading their course plan, and hoping to God somebody bothers to show up.

122. One student is complaining about being “pawned off†on graduate students. If you’ve attended a university with a large enough post-graduate program, you’ve likely had the experience of enrolling for a course which ends up being mostly or entirely conducted by somebody who is not actually a professor yet.

Every starry-eyed proto-academic must eventually find out whether or not they’re actually any good at instructing (or perhaps go into organic farming, or eBay sales). And most schools don’t have sufficient resources to put only full professors on the job.

Occasionally this ends poorly for the undergraduates, who can end up paying a fair amount of money to be somebody else’s learning experience; or it can end poorly for the graduates, who get paid in wooden nickels to try to beat knowledge into hordes of sulky undergraduates.

But it’s all part of the uniquely awful circle of academic life. For further research into the strange half-life of the grad student, I refer you to Jorge Cham’s webcomic PhD (for “Piled Higher and Deeper”).

123. OH MY GOD A GIRL IN THE LECTURE HALL!!! Unsurprisingly, very few women had been allowed to worm their way into academia

– although one or two fought their way far into the post-graduate ranks through sheer determination. Suffice to say, ladies were not a common sight at a lecture, although it’s not as if one would be stoned to death for crossing the threshold.

124. No lecture series opener is complete without a reminder that, in fact, you are in the wrong damn room.

Luther’s startling intro here is a tribute to all of my favorite lecture professors; jokers and show-men, all. My particular favorite was a lecture given by Professor Andy Szegedy-Maszak in the Classical Civilizations department at Wesleyan University, for his celebrated Greek History class. The class was held first thing in the morning, so most of the class was at best semi-conscious as he began by writing the following Greek letters on the board:

αλαλαλαλαλαλα

And then asked if anybody could tell him what it said. At long last a student raised his hand and anemically replied, “um, it says, ‘a-la-la-la-la-la-la.’â€

“Wrong!†the professor announced. “It says -” and then he uttered a piercing, Xena-like ululation that induced a room-wide heart attack.

“And that is a Spartan war-cry,†he concluded. Then he proceeded to give a very thoughtful and nuanced lecture on Spartan civilization. Bravo.

125. The passage Luther is quoting from will be referenced shortly. Note that he’s not speaking in Latin (I’d do some snotty thing like lettering in an ALL-CAPS SERIF surrounded by {imperial brackets}, if he were) – it’s all German. (Well, English, but you know what I mean.)

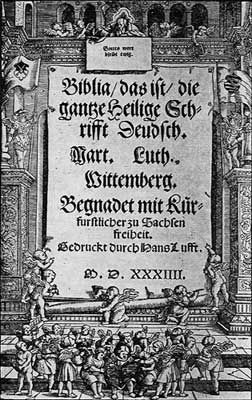

Over a century before this story takes place, Reverend Martin Luther pioneered Biblical translations into contemporary languages (“vulgate†versions, or “versions written in the horrendous vulgar tongue the peasants speak, God help them, let’s keep oppressing them by making sure only the ruling and clerical classes have access to a literal understanding of religious and legal textsâ€).

Johannes Gutenberg, in a stroke of luck, had recently managed to put together an affordable printing-press technology that meant both books and the stuff inside of them were suddenly widely available to any freshly lettered individual for a reasonable price.

But still, in educational and theological settings, Latin and the other original Biblical languages, like Greek and Hebrew, held sway. For Luther to quote John in German – and, I’ll point out, this isn’t Martin Luther’s translation he’s using, either! – is kind of like starting a lecture on Mozart by blasting “Rock me Amadeus†by Falco.

(Note: I once had a teacher start a lecture on photosynthesis by playing “Here Comes The Sun” by the Beatles. It worked.)

Obviously, while Luther’s is theoretically speaking in German, the translation is in English. To get this text, I messed around with a few modern international translations, which generally are less poetic but a tad more scrupulous when it comes to preserving original meaning.

126. A lot of people seem to like that “Iâ€, and have asked me how I found it. It’s originally just hand-drawn in solid black by yours truly, using some old woodcut lettering as a reference. Then I took a scratchy Photoshop texture brush, turned it to the eraser setting, and gently buffed the letter until it looked like an under-pressed or distressed letter generated by a woodcut or letterpress.

All of the lettering in the comic is hand-done or based on my hand, with a few exceptions. Fonts I have used but didn’t in some way generate include Aunt Mildred (the quotations at the start of the book), Porcelain (the title just after the prologue), Blackmoor (for traditional blackletter writing on various signs), and LaDanse (Luther’s handwriting).

127, 128. I’ve already nattered a bit about the Gospel of John. It contains some of the loveliest passages in the Bible – and some of the most oft-quoted (“JOHN 3:16†being evoked on ballgame fan-signs nearly as often as “GO TEAMâ€). Go read it, but only in a recent translation with scads of footnotes to keep you from getting into trouble.

This particular passage – the Good Shepherd passage – goes on a ways after Luther stops. I have my purposes for sticking to this part, as usual, but you’re welcome to read the rest.

For the Johannines, they were pretty frustrated with their own Jewish leaders – oft referred to by the blanket term “Pharisee” – who refused to support them with the whole Christ thing (the hired hand) – and very threatened by the external forces pressing down on the Jewish community as a whole, including the Romans and competing ethnic tribes (the wolf). They only had their conception of Christ to depend on – the Shepherd – and their fellow sheep. At least in my amateur and purposefully oversimplified reading.

129.“I am the Pythagorean theorem!†The other student will probably reply, “I  know the sums of the squares of my other two sides, and the sums of the squares of my other two sides know ME.†I decided that line was a bit rich for a toss-off, but man I was tempted.

know the sums of the squares of my other two sides, and the sums of the squares of my other two sides know ME.†I decided that line was a bit rich for a toss-off, but man I was tempted.

“Ach du liebes bisschen†– literally translates to “oh, you dear little bit!â€, functionally translates to “good grief!†or “heavens to Betsy!†or “goodness gracious!†or something on the order of “Ack!â€

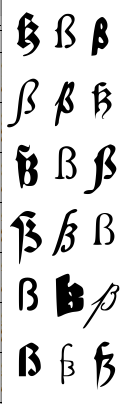

Luther is speaking it with the old spelling; the “߆character, Eszett, (indicating “s+z†– the name is just the combination of the two letters, in German) is often replaced with “ss†these days.

It first arose in the early days of printing as a ligature – a joining of two commonly paired letters to save print space and expedite hand writing. Ever seen those weird/annoying instances in older English writing where the “s†looks like an “f†unless it’s at the end of a word? Combine that character with a particular way of writing “z†and voila! Eszett.

Did I write it this way as an excuse for the note, or just because it’s fun to draw non-English symbols? Yes.