PROLOGUE / CHAPTER ONE

0-19 / 20-29 / 30-39 / 40-49 / 50-59 / 60-66

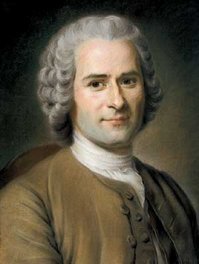

Page 0: Rousseau wrote “Emile, or, Education” in 1761, seven years before the events of this story, and both the book and its author were swiftly kicked out of France, being scandalously anti-establishment. He bounced

around for awhile and had a nervous breakdown or two before sneaking back in 1767.

Rousseau was rather cynical about modern society and its constraints, and harbored an admiration for the state of Nature, which was admittedly harsh but kept man nicely undiluted.

Rousseau is rather important to this story, although most of the characters have never heard of him, least of all the ones who agree with him. I should read more of his books, probably. He was a nasty little man with a wonderful mind.

And as for the Roman proverb, re-popularized by Thomas Hobbes (who held views almost opposite to Rousseau’s), well, it’s a nice counterpoint to the rationalist orgy above. And you know. Wolves.

Page 6-7:And this is just the old workroom. These are Avner’s favorites, not the ones he’s made, fixed, or selling. The fact that this is normally the quietest room in the house says something about the Levy family.

Furniture in that era tended towards the very simple when it came to the working and merchant classes—most of the decorations on the Levy furniture were done by the Levy father himself, as a means to test out various gold leaf patterns, wood tools, and so on.

Page 8-9:The University of Göttingen (nowadays, more properly called Georg-August-Universität) was only thirty years old, but was already one of the most vibrant universities in Germany. Like other universities, its two main departments were Law and Theology. Guess which one Luther was in.

Johann is in business; putting two kids through university is tough on the family salary even with patronage and scholarships.

So he’s a furniture trading merchant, an apprenticeship he wangled through his father’s business. Since he’s still a young buck in the biz, he gets to make all the trade trips, so a chance to visit home is rare and appreciated.

Page 13: Mom’s name is Veronika. She is, or at least has been, a Pietist, which is less strict than being a Puritan, but still demands a lot of rigor. More on her later.

The demands of children have softened her grip, a little. But that’s not saying much.

The odds are that there have been other children in the Levy family that didn’t make it past a few months old, and the age gap between the boys and Liesl probably confirms that there were a few misses before the last kid took. However, this was all completely normal for the time, and somebody of Veronika’s spiritual and physical constitution would’ve muscled through without too much drama. Other women weren’t quite so lucky.

Page 20: What’s amazing is that they actually have enough room upstairs for three bedchambers. Liesl’s nursery is about the size of a closet, though, and during the winter she sleeps with her parents.

While the boys were both away, their room was rented out. It’s been repatriated since Luther came home – another hit to the family income.

Meanwhile, Johann’s morning tune is a passage from Bach’s Goldberg Variations.

Page 21: In the room are two crucifixes, a few token clocks and watches, one print of a famous woodcut portrait of Luther’s namesake Martin Luther (unwilling inciter of the Reformation), one print of the Ten

Commandments, and an illustrated version of the passage in which Christ heals the hemorrhaging woman. Just like any boy’s room!

In the 18th century, wall decor was pretty restrained and serious paintings were only for the rich, but almost everybody could afford the cheap prints sold by street vendors, with themes ranging from religious to literary to classical to bawdy.

All of the books, with the exception of one or two devotionals and a couple of Bibles, are Luther’s student texts. Books were still very expensive despite printing technology, and large libraries were scarce outside of a few universities and the homes of the rich and eccentric. Students often had to choose between owning texts and eating hot food. Luckily Luther had a patroness to help out.

Up on the neglected hat shelf are some of the circulated pamphlets from philosophical and theological circles at the time. The 18th century was a pretty good time for zine culture.

Page 24: Fancy theology gets you nowhere with the guy who’s been smelling your night-time farts for the past quarter century.

Page 26-27: Patronage was the best, but often most agonizing, way of getting through your education. Patrons could demand a lot of mindless boot-licking in exchange for minimal funding, much less full support. Or, conversely, you could be adopted almost as a member of the family. Either way, you were walking a wobbly line in which high performance and loyalty was demanded of you, regardless of how tired, hungry, or distracted you were.

If you were without family connections, patrons were often your only means to get through your education and acquire a decent position in the Lutheran church (the only truly legitimate career for a theologian outside of a few very limited professorships). Absent that backing, you were looking at a lifetime of poverty and obscurity in a backwater parish.

Patrons could be professors, your family’s employers, the local prince, a high-ranking cleric, or, in Luther’s case, a female Baron (“Baronin” – a “Baroness” is the wife of a Baron).

Luther was the star pupil at the local Latin (grammar) school, and so came up for the honor by way of Pastor Altmann’s recommendation to the Baronin of Konstanz.

Page 30: Tutoring for the children of aristocrats and upper bourgeois – often your (potential) patron – was generally considered to be hell on earth. You lived in a bizarre class limbo, treated as something of a lowly house servant, yet expected to teach the children everything about being upper class, from etiquette to fencing to French grammar.

One major slip-up and your prospects were toast…do a good job, and you could be a made man. In the meantime, the money was poor, the emotional stress astronomic, and the work totally dispiriting. It induced suicidal urges in more than a few cash-strapped scholars of the day.

You can still see this awful system in place in the Stendhal novel The Red and the Black.

Page 31: Dad’s outfit is sooooo 1750. Johann, meanwhile, is wearing a lovely contemporary silk overcoat. Somebody in the family has to have style.

As for dad, like most craftsmen of the time, Avner works in the same house as he lives – this meant that most days were spent wearing the period equivalent of a bathrobe and bunny slippers.

Most people owned only a very few outfit elements suited for outerwear – generally made of wool or printed

cotton in a practical palette – which would last them for ages and be washed very infrequently.

In contrast, you could own dozens of basic chemises or under-gowns, which would be cycled through until utterly unwearable, then hauled out two or three times a year and subjected to the enormous, never-ending group torture session known as The Great Wash.

Mention wash day to Liesl, and she will probably start crying outright.

Page 32: There are reasons both personal and cultural why he ran off with a Christian girl.

Culturally, the Jewish community in general was in a state of upheaval around this time, with a lot of reformers trying to integrate more into the local culture and join the longstanding Jewish intellectual tradition to the larger goals of the Enlightenment. So there was plenty of room for confusion, conflict, and unhappiness, above and beyond the usual flak. Avner’s family didn’t cotton to it all, and with no local progressives to latch onto, marrying goy was an alternative.

As for why Veronika would marry him…

Page 33:I was going to have a whole scene with the girl who helps out in the house that was basically an excuse for me to talk about household candle-making, which involved giant pots of fat and very little fun.

I commissioned Anne to find me a dog, with the stipulation it be a mutt. She found this nice critter, who is probably a mix of breeds that have no excuse to exist in 18th century Germany. I don’t care, he’s cute.

They got Hugo to chase the rats that generally infest chicken-yards, but he’s much better at bothering the chickens.

Page 34: There was rain recently, or else Luther wouldn’t even think about walking in the alley groove. Bad things went there.

Luther’s town is a dense old medieval village on a mid-sized east/west trade route. It’s encircled by a couple of disintegrating patchwork stone walls, so carriages and such can’t get in or out at night, but on foot you can do it without much trouble.

Page 34-5:This is a pretty remarkable place for a town of this caliber, and is one of the few things the outer world knows the town for. The shop functions as a bookstore as well as a for-charge lending library – Frau Vogel lets Luther rent the obscure books he orders, with the lending fee going towards an eventual purchase. Very eventual.

The Vogels have been running this place for ages – maybe there was a seminary in town back in the day. Herr Vogel passed away a few years ago, and Frau Vogel is a childless widow who nonetheless keeps it running.

There are a lots of religious texts in here, obviously. You have to ask for the trashy stuff under the counter. Ever seen 18th century porn? Yeah, it’s weird.

Page 35:Yes, Bite Me! readers, that’s Lucien. The visual translation between drawing styles was fun to figure out.

As for the other aspects of his Lucien-ness, well, it’s up to you to piece together.

Page 36: Luther was basically up for his PhD back at Gottingen. By that point you were occasionally delivering lectures of your own material.

Lucien’s career isn’t that odd – there was money to be had in tutoring undergraduates for specific courses and subjects, both through colleges and privately. Couple that with some teaching at the local schoolhouses, taking official lecture notes, and other intellectual piece-work, and you could squeak by.

Very tangentially, St.Yves is in Bretagne, the Northwestern sticky-out bit of France, and the part with the closest cultural connection to Britain, which maybe explains a lot about Lucien. Saint Yves is the patron saint of lawyers.

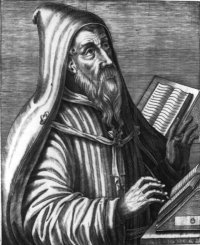

Page 37: Saint Augustine of “Confessions” (best known for saying “Oh Lord, give me chastity…but not yet”). A 4th century cornerstone of Western Christianity who through his rhetorical and administrative skills managed to do away with quite a number of competing Christian philosophies (or “heresies” as the winners call them) and other religions beside. Adored by Catholics and Protestants alike, and still a good read.

See, Luther is capable of being something other than cranky! Still sarcastic, though.

Page 38:Luther’s mom has reason to narrow her eyes at French things. If a thing could be made, acquired, style, or iterated in a French way, from France, it was trendy, and probably morally dissipated.

Familienwald roughly means “Forest of the Family”, which is an unusual town name, but not outright weird.

The Quartier Latin (Latin Quarter) is the old University district in Paris, adjacent to the South side of Seine. Full of roving students and intellectuals, and as a result chock-a-block with booksellers. If you go there today, the walkways along the river are lined with blue book carts selling everything from reproduction movie posters to rare first editions of novels.

Page 39: Family genealogies were a big thing, and you could make some cash off of compiling them for rich folk. Not particularly enthralling work, though, and you had to have nice handwriting.

As for the “local prince”: The Holy Roman Empire (jokingly referred to as “Neither Holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire” by clever history teachers the world over) could count over a half dozen individual Germanic states as members, not to mention several non-members that it regularly went to war with.

Most people lived within the domain of a local noble or a penny-ante royal, essentially a governor with a pedigree, who ran his or her tidy chunk of territory with some nominal obedience to the next rank up on the chain. This prince or duke or what-have-you would often oversee the funding of the local university, coordinate

with the high-end clergy, and generally try to keep the metaphorical trains running on time.

As for the details of this particular location, I’ve intentionally kept Luther’s home town vague. The fact that he went to Göttingen suggests Saxony.

“refused a lecture post” – this part of academia hasn’t changed, really. Finding and keeping a decently-paid professorial position involved equal amounts of backstabbing and sucking up. And in an era devoid of speedy communication, figuring out who might hire you in another town and getting there in time was tricky.

Page 40: The free tables were a mainstay of Universities at this time. Scholarship students would be awarded a place at cafeteria tables specifically designated “free of charge” for one or two meals a day. The food was not fantastic (think “spam, spam, spam on spam”), but it would keep you alive on the cheap.

The Rector was the rough equivalent of the college president: in charge of PR, overseer of all the committees and bodies within the school, chair of the Senate, head of the disciplinary Court of Justice, and so on.

Page 41: it’s not a working clock. Alas.

Page 42: As mentioned before, Medicine was one of the major disciplines, along with Law and Theology. You could theoretically switch, but then, nobody cared too strongly how long you stuck around – students would drift in and out, a large number never making it through a particular degree. Hans Ruder is probably one of those Super Seniors you see lying around the quad playing hacky sack and hitting on pre-freshmen.

They’re likely not drinking water (not even Liesl). Water at the time was often unsanitary and foul-tasting, so in many places you would have “small beer”, a very diluted, mooshy ale made from the second or third take on a single batch of brewer’s mash.

This wasn’t looked on with any particular horror, even by religious folk, because alcohol content rarely hit 3% – it made normal ale look like jet fuel in comparison, and it was especially pushed on children and servants. It was particularly popular in colonial America. John Adams pretty much lived off the stuff.

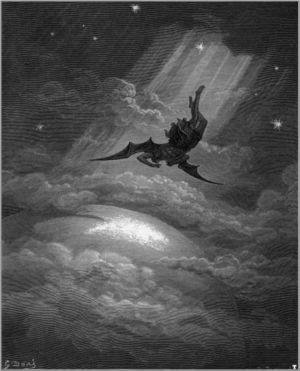

Page 44: Yeah, Lucien’s not being particularly canonical, here – even Milton at least makes

Lucifer rebel out of jealousy for the coming Christ. Romanticism and its big ole focus on sexy, brooding, tragic individualist heroes didn’t exist yet, but Lucien probably met Percy Shelley when he was a teenager and caused it all.

Page 45: And then after the ANCHOR escapement, this guy named Graham figured out how to jigger it so that the constantly changing temperature of the pendulum itself wouldn’t throw the clock off-rhythm (by hollowing out the bob and filling it with liquid mercury), and then this guy Harrison refined it still further in 1761 and if Luther and Johann hear this lecture one more time they will scream.

Page 46: Little bits of the main shop, here, closed up for the night.

The only other room on the ground floor, besides the study, is the kitchen and its pantry in the back of the house. Only the better-off or non-merchant types could boast a fully residential house with a separate parlor and dining room.

Page 48: That pocketwatch on the right side of the table? Totally has a compass attached to the glass lid. The iPhone of its day.

Lucien is saying “Good night, Colleague.” Because he’s a complete dweeb.

Page 49: And Luther is saying “Good night, companion.” Because he’s a complete dweeb.

Page 50: Buildings referenced from some great medieval houses that are still standing in Central Germany. Bless you, Flickr. Bless you.

Page 53: To be honest, the whimsically-inclined daughter of a converted Jewish clockmaker and an ex-bourgeois Pietist living in a small trade village in 18th century Germany probably doesn’t have dazzling prospects in her future. Luther can angst all he wants, but his sister has it worse. Being a girl in just about any era of the past? No good.

Page 54: It’s surprisingly hard to find good reference for carriages – or at least for the sorts of carriages used by normal people rather than crazed Hungarian princes. In the end I just conceded to destiny, found my

DVD of Sleepy Hollow, and did some freeze-frame flim-flammery on the opening scenes where Martin Landau gets his head sliced off.

So if you’re an 18th century carriage enthusiast and can tell exactly where I screwed up – don’t judge me too harshly, and send your hatemail to Tim Burton.

The horse gear, on the other hand, is from an actual source. So I feel good about that.

Lastly, “Tausend Dank” = “A thousand thanks.”

Page 55: Luther just made a very bad Spanish pun. I apologize on his behalf.

Page 59-63: no notes here. I don’t think the horrors of 18th century childbirth and miscarriage need to be gone into with much detail.

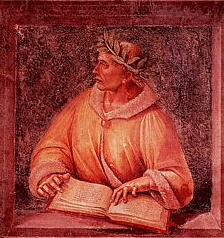

Page 64: That would be a book of Publius Ovidius Naso, aka Ovid, the Roman poet best known for the Metamorphoses, a big, bright, crazy compendium of poems retelling classical myths, all featuring, well, metamorphoses. Go read the one about Actaeon and Diana and come back with your book report.