Notes for Pages 80-89.

< 70-79 | Notes Index | 90-99 >

Page 80: The sacristy is sort of God’s own cross between a green room and a supply closet, where materials for worship are stored, and where the vestments are put on, and taken off for services. The sacristy is generally either behind or to either side of the main altar, and most of them have these big, wide, flat sets of drawers in which you can lay out a whole robe, wrinkle-free.

In short, a great place to turn into a cataloguing room. And from Ariana’s slip-up, you can learn that the altar now doubles as a reference desk! I know some reference librarians, I have to earn points with them somehow.

Page 81: And the dirt will out! More on what Luther did to totally screw up his academic career, coming soon.

Lucien’s job is sort of Head Procurer. His trips out of town involve both building the library’s collection, and finding potential University employees. No craigslist back then.

Page 82: The old Groucho Marx deal – “I don’t want to belong to any club that will accept me as a member.” A university is an institution with a lot of very neurotic humans inside and very little tangible output, so it’s impossible to attend one or work for one without at some point losing respect for the institution, yourself, or both.

The sign reads “Bibliothekscatalog” (Library Catalogue). No idea if that word existed at the time, but Germans are good at making up words, so let’s give it a free pass, hey? At any rate, it’s locked, as it generally is, and people can leave their books on the shelf.

Ariana’s holding still more Virgil.

Page 84: Not that big an office for the era, really. No more than a twelve-foot ceiling, and the waiting room Luther was standing in is pretty much an outsized closet. The painting above his head in the second panel has an actual source that I now completely forget; he’s some Dutch astronomer or something. The painting in the office I made up, but it’s probably some Magna Carta type scenario. Schools inherit weird paintings.

Page 85: The bust is the great philosopher Aristotle, whose early ideas on scientific method kept a stranglehold over Western thought for a bit longer than was strictly flattering. The telescope thing is, actually, not a telescope, but a spyglass (think Horatio Hornblower instead of Galileo). The skull is real and yes, you did see a gun in that last page. Meanwhile, I totally forgot the panelling on the desk. Doh.

As for Rector Nolte, he likes to get right to the point.

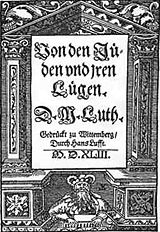

Page 86: The Jews and Their Lies, written in 1543, is Martin Luther’s most shameful legacy, and without a doubt one of the most  hateful documents ever to enter Western history. It’s still the source of a fair amount of anguish and repudiation in the contemporary Lutheran church, particularly in the continued wake of the Holocaust.

hateful documents ever to enter Western history. It’s still the source of a fair amount of anguish and repudiation in the contemporary Lutheran church, particularly in the continued wake of the Holocaust.

In earlier life, Martin Luther was a bit more benevolently disposed towards the Jewish community, espousing the hopeful belief that the reason so many Jews remained so implacably Jewish was that the shamefully debauched Catholic church could hardly bring itself to salvation, much less anybody outside the faith.

However, when the Jews did not convert in mass numbers upon hearing of his proposed reforms to the church, his frustration joined forces with a creeping bitterness and paranoia and produced an attitude more along the lines of “kill them all” than “suffer them to come unto me.” Sadly, several municipalities took the hint.

Luckily the text proved a little too crazy-eyed for the 17th and 18th century public, and you wouldn’t have found many recent mass printings in our Luther’s time. Who knows where his mom got her copy, but she doesn’t let these things get in her way.

Page 88: “Sei’s drum!” roughly translates to a breezily uttered “Anyway!”

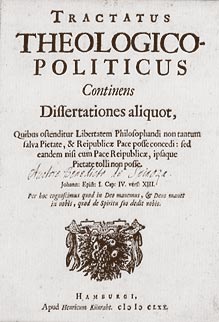

Baruch or Benedictus de Spinoza was a 17th century philosopher, whose works include the Ethics and the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus. He came from the Portugese-Jewish community in Amsterdam. The Inquisition had served to exterminate or drive underground much of the Jewish population in Portugal, so many families jumped ship to the more tolerant North lands (although with no little guilt for those left behind). As a young man, Spinoza was considered one of the up-and-coming theology students of his community. Unfortunately he didn’t limit his inquiries to Judaic schools of thought, and before long was rubbing elbows with rationalists and taking Latin lessons from notorious characters.

At the ripe old age of 23, he was goaded by some fellow youngster into confessing his lack of traditional faith and was excommunicated from the community, something he accepted with a rather cool, passive ease (a lifelong trait which appears to have driven many people absolutely bats).

He took up optical lens-grinding to pay the bills, never formally converted to Christianity (despite the social convenience that would have offered) and spent his spare time producing absolutely radical, nearly mathematical philosophical texts that still caused ire a century after his early death in 1677.

I’m not a Spinoza expert – his work is notoriously tricky, and I am but a Lit major, but here are some central points of what he proposed:

1) There is only one substance in the whole universe, and it is infinite and eternal.

2) That substance can be called God, or Nature (Deus sive Natura).

3) Everything in existence is simply that substance working in a particular way (mode).

4) The mind is an aspect of the body.

5) Our senses are inadequate sources of information.

6) There is no free will, because everything responds in the only possible way it can given the sequence of events, but we can have an understanding of our actions.

7) Everything wants to keep existing, and will act solely for that purpose, although the actions won’t necessarily be the right ones to achieve that purpose.

8) Overcoming passions and achieving a rational detachment from the trials of daily life is the best state of mind for truly acting for your best long-term benefit, which

9) will ultimately benefit all of society, since self-benefit is best achieved by reaching harmony with others.

10) God cannot love a person (because God is the universe, not a separate, conscious being), but a person can love God by trying to understand the world around them through reason.

Not exactly a bag of warm fuzzies, and certainly not in line with any of the major religions. The whole “God…or Nature!” bit ruffled some feathers, but while he came close to getting skinned a few times, he was also an active acquaintance of many of the intellectual lights of the time. Some of them nervously scratched off his return address on the envelopes to avoid losing their funding.

By Luther’s time, thinking like this, or at least a little like this, was gaining steam. Traditional state religion and monarchy by divine  right were being increasingly jabbed at by people like Voltaire and Rousseau, who, unlike the famously non-confrontational Spinoza, were actually interested in making waves. (Spinoza’s personal seal was a thorny rose – Spinoza means “thorn”, wonderfully enough – garnished with the Latin word for “Caution.”)

right were being increasingly jabbed at by people like Voltaire and Rousseau, who, unlike the famously non-confrontational Spinoza, were actually interested in making waves. (Spinoza’s personal seal was a thorny rose – Spinoza means “thorn”, wonderfully enough – garnished with the Latin word for “Caution.”)

In our own time, Spinoza continues to attract his fans, especially people working in neuroscience and advanced physics.

And cartoonists, apparently.

The IEP has a much better run-down on Spinoza than I can provide, and includes a great bibliography. Go over there if you want to know more.

At any rate, for Luther (a kid with Jewish background, no less) to write a theology dissertation on Spinoza and conclude with “Spinoza is right”, not to mention blowing off his faculty sponsor to do so, is tantamount to committing career suicide in a profession where you’re expected to go into the clergy, even if you just want to be an academic.

By which tangent I’ll note that, yes, Rector Nolte is probably ordained.

Page 89: Ha! Robes! Academic robes had gone out of daily use in most Universities by this time, although a few persist in requiring it even today. But for formal events they would be hauled out.

The black base, the roba, was originally taken from the time when students were almost all in religious orders, and black is still the norm, unless like me you went to Wesleyan University and had to wear blinding scarlet at graduation.

At various times and places stripes, hoods, stoles, special lining, the cut of the sleeves, mortarboards, and the like could all indicate that  you were an officer of the University, a graduate of a certain school, a degree-holder in an particular topic (at least one source suggests that the current official color for library science faculty is “lemon”) and so on. Surprisingly, America is the most fiendishly absorbed with the subject; Europe can’t quite be bothered. We thirst for fake ancient tradition, apparently.

you were an officer of the University, a graduate of a certain school, a degree-holder in an particular topic (at least one source suggests that the current official color for library science faculty is “lemon”) and so on. Surprisingly, America is the most fiendishly absorbed with the subject; Europe can’t quite be bothered. We thirst for fake ancient tradition, apparently.

Luther has rakishly left his hood at home. He probably had it washed in anticipation, and the dye in the lining ran, or it was still damp, or he left it under the bed, or something. Because I enjoy drawing stoles, I randomly decided that Göttingen theology department uniform would require stoles. You get to do this when you make a comic.