Notes for Pages 150-159.

< 140-149 | Notes Index | 160 – 169 >

150. BATS! I learned a lot about bats for this page, because it seemed like fun. For example, the basic difference between microchiroptera (wee bitsy bats) and megachiroptera (big damn bats). Big bats tend to be fruit-eaters and have longer snouts; little bats are the pug-nosed ones who eat bugs, as in panel six.

151. WARNING:Â SPINOZA BABBLE BELOW!

Ignore my rambling and skip down to the other notes for this chapter by clicking here.

“Like Spinoza” – as I noted before, the philosopher Spinoza was a Jew (but only by upbringing and heritage), and an atheist (but only in popular conception) and regularly bullied for not becoming a Christian (since, after all, so many of other people already were, and since his knowledge of Christian scripture and theology was fairly formidable).

For all his personal aversion to organized religion, though, he seems to have had a necessary willingness to play along when people’s best interests (as opposed to their prejudices) were concerned, and to have maintained a respect for religious sentiment and behavior at its best; a famous and relatively well-confirmed anecdote exists in a biography of Spinoza written by the minister who took over the local church some years after Spinoza’s death –

“It happened one day that his landlady asked him whether he believed that she could be saved in the religion she professed: He answered,”Your Religion is a good one, you need not look for any other, nor doubt that you may be saved in it, provided, whilst you apply yourself to Piety, you live at the same time a peaceable and quiet life.” (Colerus 1906: 41)”

Professor J. Thomas Cook of Rollins University has written a nice essay on what the hell this actually means and why Spinoza might have said it, which you can read here.

Less comforting, however, is Spinoza’s correspondence with a former student, Albert Burgh. Burgh left Spinoza’s tutelage and ended up jumping with both feet into the Roman Catholic church. He promptly wrote back to his former teacher and insisted on his conversion, in language heavy on the fire and brimstone (the phrase “your pestilent heresy” comes into play).

Spinoza’s response starts off with “I wasn’t going to write back to you since you’re obviously a bit crazy right now and I suspect it won’t do either of us any good, but all your friends really want me to give it a shot so here we go” and then pens this backhanded little universalist paragraph (all quotations translated by R. H. M. Elwes in 1901):

“I will not imitate those adversaries of Romanism, who would set forth the vices of priests and popes with a view to kindling your aversion. Such considerations are often put forward from evil and unworthy motives, and tend rather to irritate than to instruct.

“I will even admit, that more men of learning and of blameless life are found in the Romish Church than in any other Christian body; for, as it contains more members, so will every type of character be more largely represented in it. You cannot possibly deny, unless you have lost your memory as well as your reason, that in every Church there are thoroughly honourable men, who worship God with justice and charity.

“We have known many such among the Lutherans, the Reformed Church, the Mennonites, and the Enthusiasts.”

He then goes on, in one of my favorite bits of his writing, ever:

“As it is by this, that we know “that we dwell in God and He in us†(1 Ep. John, iv. 13), it follows, that what distinguishes the [Catholic] Church from others must be something entirely superfluous, and therefore founded solely on superstition.

“For, as John says, justice and charity are the one sure sign of the true Catholic faith, and the true fruits of the Holy Spirit. Wherever they are found, there in truth is Christ; wherever they are absent, Christ is absent also. For only by the Spirit of Christ can we be led to the love of justice and charity. Had you been willing to reflect on these points, you would not have ruined yourself, nor have brought deep affliction on your relations, who are now sorrowfully bewailing your evil case.”

Later on he goes off at Burgh’s apparent intellectual contradictions with a more visceral oomph. It’s really a wonderful (and entertaining) letter, written in a cool and even-handed tone. Various readers have taken it as an anti-Catholic tract, but it’s fundamentally an anti-hypocrisy tract; as various passages suggest, Spinoza could’ve written essentially the same letter to Burgh if he’d converted to Lutheranism or even Islam.

Last quotation:

“But assume that all the reasons you bring forward tell in favour solely of the Romish Church. Do you think that you can thereby prove mathematically the authority of that Church? As the case is far otherwise, why do you wish me to believe that my demonstrations are inspired by the prince of evil spirits, while your own are inspired by God, especially as I see, and as your letter clearly shows, that you have been led to become a devotee of this Church not by your love of God, but by your fear of hell, the single cause of superstition? Is this your humility, that you trust nothing to yourself, but everything to others, who are condemned by many of their fellow men? Do you set it down to pride and arrogance, that I employ reason and acquiesce in this true Word of God, which is in the mind and can never be depraved or corrupted?”

What I enjoy in this is that Spinoza never displays any animus against religious faith that is based in love and/or reason. He instead consistently deplores the superstition, fear, circular reasoning, and political/economic influences that he sees at play in religious organizations of all stripes, and makes a determination that the good among the faithful are good because of some universal aspect of godliness, not because of the particulars of their affiliation.

Read the whole letter (along with Elwes’s translations of most of Spinoza’s extant correspondence) over at the Library of Liberty.

On the whole, you can see why Luther is fond of the guy.

Page 152. “If he wants to be a Jew…then, by God, she’s his mother!“

Luther is making a little joke here about one of the more  interesting legal structures in Judaism: the law of matrilineal descent. (Well, he’s also making a cultural joke about Jewish mothers, which strain of stereotype humor apparently dates back to Eve, but I digress.)

interesting legal structures in Judaism: the law of matrilineal descent. (Well, he’s also making a cultural joke about Jewish mothers, which strain of stereotype humor apparently dates back to Eve, but I digress.)

The principle of matrilineal descent says that a person with a Jewish mother can be considered Jewish as well, while a person with a Gentile mother – even if their father is Jewish – is a Gentile. This can seem odd in light of the predominantly patriarchal structure of the Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition.

In Deuteronomy 7, the Jewish population is warned against intermarrying with other tribes:

“3 Do not intermarry with them. Do not give your daughters to their sons or take their daughters for your sons, 4 for they will turn your sons away from following me to serve other gods, and the LORD’s anger will burn against you and will quickly destroy you.” (New International Version)

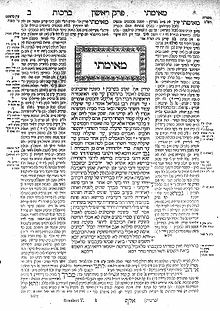

This passage is taken up in the Talmud (“the Study”), a complex collection of ancient rabbinical debates about Judaic law (Mishnah) and tradition (Gemara). Since the issue is raised in the Torah, it’s debated in the Mishnah, in a section called the Kiddushin.

The Talmud is difficult to parse online, since it’s essentially a collection of ancient legal arguments written in the margins of books over centuries and its layout reflects that eclectic form of debate. It’s also difficult to parse in print, because it’s a collection of ancient legal arguments written in the margins of books over centuries.

Luckily we have Dr. Susan Sorek of the University of Wales in Lampeter to explain it all for us, and you can read her article on the subject here.

Compatibility with Roman laws surrounding inheritance and citizenship, ethnic purity, the growing importance of Jewish women due to their supposedly greater inclination to virtuous charity than Jewish men, the destruction of the Second Temple, the changing nature of Gentile conversion, mother figures in scripture…the only real consensus is that the matrilineal descent became widely accepted after 70 CE or so and hasn’t really been challenged since.

Anyway you look at it, Luther is basically boned. Having a Jewish mother was unfortunate but not socially prohibitive in 18th century Gentile society; having a Jewish father, a lot tougher. And in Jewish society, as the matrilineal stuff above suggests, Luther wouldn’t be considered a Jew until he formally converted. Which would, yes, involve circumcision.

(And, by the way, pretty much nobody was circumcised for reasons other than religion or disfigurement before 1900, when germ theory hit and everybody got a little overexcited. Today it’s finally being formally discouraged as a medical practice.)

Page 153-159. You’re on your own here, kids. See you in the next chapter.