Notes for Pages 130-139.

< 120-129 | Notes Index | 140-149 >

130. And yet, despite the presence of the esszet, I use the modern American spelling for words like “parlorâ€. I’m an awful person.

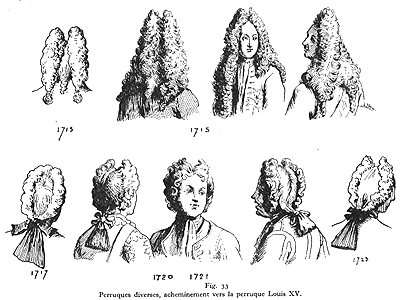

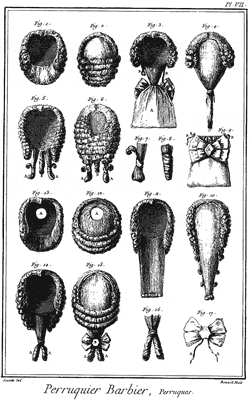

134. Ah, the formal wig! Possibly the most confusing aspect of old-time fashion to us postmodern types. Where did they come from? When and why did people wear them? Why were some of them white, and others not? Other people are better qualified than I to answer that question, but hey!

The perruque, peruke, or periwig wig – modern-era European wigs – got their real start in the Baroque period. Various royals had worn them before to add a bit of flash or cover up a bald spot, but the French monarchy really brought them into style earlyish in the 1700s, and eventually every fellow wishing to attain a station higher than fishmonger had to have one around the house somewhere.

Initially they were ginormous long, curly, and poofy affairs called “full bottom†wigs. Then in the 1720s or so wigs enjoyed a period of wild mutation and general adoption into forms more convenient for the active lifestyle and skinnier pocketbooks of the middle classes.

One of the models which gained popularity particularly among the bourgeois was the stylish and affordable perruque en bonnet, the kind of wig we see most of the faculty members wearing in this scene. In previous scenes we’ve also witnessed Luther wearing the perruque en bourse, a bagwig, which is basically the bonnet model with a handy little pocket for your fake ponytail. Apparently these were initially worn in situations that were largely informal but still required public decorum – fetching the mail on a windy morning, say – but were eventually co-opted by the fancy classes, sort of like designer jeans.

The best wigs were made from human hair, but many were made primarily of horsehair. The structure underneath, which attached to your own personal head, varied by cost and construction; much like the arms race between razor manufacturers today, wigmakers promoted the particular comfort innovations of their product.

Color: the origin of the white/gray/light blue wig as fashion standard is a bit  more of a mystery beyond the fact that those early royal wigs were designed to give the wearer a wise, distinguished look. Horsehair is particularly difficult to bleach to a consistent tone, so powdering became the method for achieving that ivory effect. Powder could be derived from a number of starchy sources, and the devotedly foofy would lightly tint it and perfume it. Luther had a properly white powdered wig, once: the dog ate it.

more of a mystery beyond the fact that those early royal wigs were designed to give the wearer a wise, distinguished look. Horsehair is particularly difficult to bleach to a consistent tone, so powdering became the method for achieving that ivory effect. Powder could be derived from a number of starchy sources, and the devotedly foofy would lightly tint it and perfume it. Luther had a properly white powdered wig, once: the dog ate it.

By the time this story takes place, wigs were eeever so slowly losing popularity, and a few more naturally-toned wigs were entering the marketplace. Wigs began to peter out after the French Revolution, for obvious reasons. Then for a brief period a few poets and youths powdered their natural hair, and then everybody gave up.

For those interested in a closer analysis of the rise and fall of the wig, I recommend Michael Kwass’s wonderful article “Big Hair†at the History Cooperative; for those of you interested in more visual sources, head over to the wig history section at the Costumer’s Manifesto.

Oh yeah, the Rector’s Mansion. Yanked and altered from several different sources depicting early Baroque mansions in the Czech Republic. It was built as an original part of the campus, but it was not the first building of note to exist in this location; it used to be a noble residence. More on that later, if it ends up being important.

135. I just really wanted to draw a Wall of Hats. Can you blame me? No, you cannot.

The faculty members: are named for two of my professors. They bear them no resemblance whatsoever; if they did, Kleinberg would be wearing Scooby Doo socks, and Arnold would be saying something completely nuts. Oh wait.

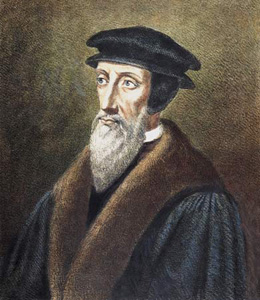

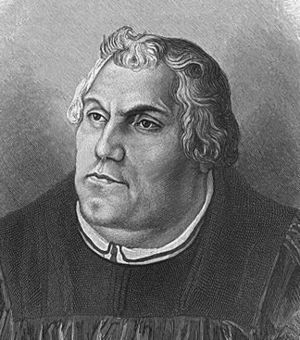

136.Little Calvinist prig: a reader asked, isn’t Professor Kleinberg a Calvinist, too? The answer is that Protestantism at the time was only barely less complex than it is now.

Kleinberg is most likely a Lutheran, although it’s also (faintly) possible he’s Catholic.

John Calvin and Martin Luther, while both instrumental in the creation of  Protestantism, took rather different approaches to the concept, and their followers also diverged.

Protestantism, took rather different approaches to the concept, and their followers also diverged.

Both Calvin and Luther objected to the notion that you could earn points with God by performing specific tasks (which included slipping your priest a fiver); you could only please the Big Guy by having faith, which could only be given to you by God’s consent (grace).

The Calvinist, or “Reformedâ€, churches threw out most of the worship style and church structure of the Roman Catholic church, focusing on predestination and “total depravity†– the idea that you come out destined for heaven or hell and could do nothing about it – and “original sinâ€, that everybody is born inherently sinful. American Puritans are a fine example of this theology.

The Lutheran church took a somewhat softer approach, keeping many of the  core ideas from Roman Catholic worship and order. Unlike the Calvinists, the Lutherans didn’t think you could be born pre-damned. You have to turn down every single opportunity for grace that comes your way to earn that particular ticket; and those opportunities come courtesy of Christ’s sacrifice, not because of God’s all-powerful spreadsheet.

core ideas from Roman Catholic worship and order. Unlike the Calvinists, the Lutherans didn’t think you could be born pre-damned. You have to turn down every single opportunity for grace that comes your way to earn that particular ticket; and those opportunities come courtesy of Christ’s sacrifice, not because of God’s all-powerful spreadsheet.

Lutheranism was somewhat more receptive to the rationalist Enlightment fiddle-faddling, as well, which made it more welcoming to the only loosely devout, who enjoyed dancing or staying up past ten.

Hence I’ve given you a horrible stereotype in which a metrosexual lush of a rationalist Lutheran theology professor is bitching about his uptight secretary, who probably scribbles righteous little Calvinist screeds in tiny script on the margins of all of Kleinberg’s correspondence.

137.Formula of Concord: I am the only person who will ever think this is hilarious. Here is why it is totally hilarious:

The sacrament of the Eucharist, wherein a priest blesses bread and wine and congregants consume them in an act we call Communion, was taken rather literally in Catholic theology. (And still is.) When the sacrament is performed, the bread and wine are transformed into the flesh and blood of Christ, full stop. They may still TASTE like bread and wine, but in essence, you’re eating Jesus. This doctrine is called transubstantiation.

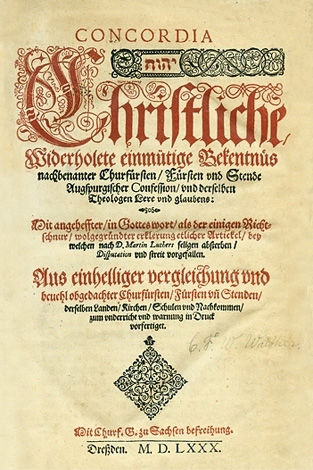

The Formula of Concord was an important piece of Lutheran paperwork, written in 1577, which lays out a great number of principles in twelve articles. Article VII deals with the Eucharist, and makes the argument that transubstantiation is silly. The Eucharist is spiritually symbolic of Christ’s flesh and blood, but you’re still eating bread and wine. This doctrine is called CONsubstantiation.

It is why, growing up as a Methodist, I was allowed to wander up to the altar after church was over and wolf down leftovers from Communion. While my father, as a Catholic altarboy, regularly had to risk life and limb to make sure that not a single crumb of the Host ever hit the floor.

So Luther’s making a rather waggish joke about lack of contact with “real flesh and blood.†Isn’t it hilarious.

I KNOW YOU ARE LAUGHING.

138. You can probably tell that a guy has a crush when, rather than offering to fetch somebody from the room full of medical faculty, he mentions the girl. Twice.

139. Every university inherits weird collections that they can’t use, but can’t turn down. This room houses some of that effluvia.Bookbinding was still a flourishing private trade, and a bindery would certainly be a busy place to grow up. A lot of books were sold unbound so that the purchaser could then have them bound to suit their budget and preference. Nolte’s father worked in a comparatively rural area, but served a number of rich country patrons.