Notes for Pages 140-149.

< 130-139 | Notes Index | 150-159 >

140. Another fairly typical route to education for the bourgeoisie. Luther was recommended to a patroness by his Latin-school teacher and his local clergyman; Nolte was shipped wholesale to his dad’s biggest local customer. Like a fruit basket!

And, in alternating panels: some of the University’s zoological collection. A magpie, some moths referenced from a case at the Natural History Museum in Washington D.C., and what looks to bea collection of various worms and parasites. (The labeled jar: canine intestinal worms.) Oh, and an actual bit of living nature: a Norway rat, Rattus norvegicus.

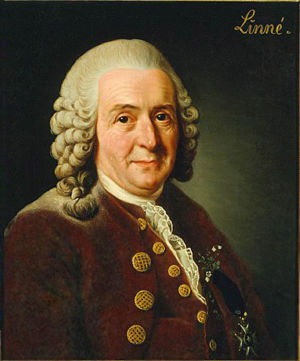

Two-part Latin names for animals – the convention called binomial nomenclature – was brought into vogue by a Swedish naturalist named Carolus Linnaeus. He only died in 1778, ten years after this story takes place. He had much the same universally adored status as Stephen Hawking does today, and modern biologic classification is a direct descendant of his work.

Doubtless you’ve had to memorize some mnemonic for Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order,

Family, Genus, Species?

141. A peek back into Rector Nolte’s academic career. Anthropology as a concept has been around at least since Herodotus – who attempted to describe some of the many farflung tribes of mankind in his work, although often he did so without any actual traveling on his part, instead relying on oral history, legend, and fragmented written accounts now lost to time. The results are sometimes amusing, as we learn from Kate Beaton.

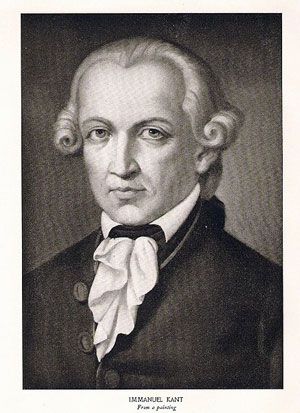

Anthropology as an academic discipline – including the kind of religious survey Nolte seems to have undertook – really got its official start during the mid-to-late 18th century. Immanuel Kant spent a great deal of time parsing through secondary sources to compile information about his own German culture and ultimately ended up teaching a university course on the subject around 1775, just a few years after this story takes place.

Nolte’s undertaking is fairly progressive, though (especially since it happened in the 1740s); actually hitting the road and meeting or interviewing religious celebrants of different denominations would have been a punishing endeavor.

As noted, he’s depicted here visiting a German Lutheran country church, a Roman Catholic church (probably in Bavaria), and some Dutch Reformed folks, also known as those pesky Calvinists, a few of whom were still practicing in Quaker-like settings.

Russia would be a point of interest for the Russian Orthodox church, which was enormous and pervasive and still centuries away from that bothersome socialism business.

142. That’s a pagan statue in panel three, there, but the sackcloth dumped on her head sure makes her look like the Virgin.

144. Recognize the bed? And the floor? And the gun?

145. And the hallway? And the outfit?

I have now officially spent too much time researching 18th-century lanterns, by the way. Officially too much time.  Most involved four to six flat panes of glass held together by brass or other common metal, with one hinged door.

Most involved four to six flat panes of glass held together by brass or other common metal, with one hinged door.

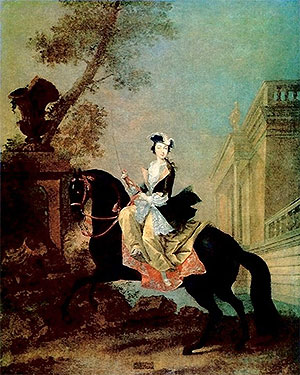

I have also now spent too much time researching saddles. Ariana’s loading up a very classic kind of English hunting saddle which is still in wide use. And it’s an astride saddle, aka a man’s saddle.

Most women at the time were using special ladyfied side-mounting saddles, by the way, unless they were royalty and nobody had the courage to give them guff about it (Marie-Antoinette and Catherine the Great both regularly rode astride). But astride saddles for woman didn’t really gain acceptance until trousers did.

146. And remember those wolf statues?

The town I use for a lot of street reference in Familienwald is the picturesque and well-preserved Czech tourist town of Ceský Krumlov, pictures of which are widely available on Flickr.

148. Panel three has confused some folks. They’re still standing separately (as depicted in panel four), but I wanted to juxtapose the two characters.