Notes for Pages 90-99.

< 80-89 | Notes Index | 100-109 >

Page 90: The little banners hanging beneath each faculty member have the Göttingen seal on them. Heaven help the poor woman who had to embroider them on. I couldn’t find out if they actually used this seal at the time, but what the heck.

Page 91: Those hands are all Steve Lieber. Steve’s a mensch.

Page 92: BZZZZZZZZTwrong.

Page 93: Colleges typically had their own internal justice system, and it was ominously called the Court of Justice. Charges could range anywhere from your typical “drunk and disorderly†college behavior, to very serious offenses like the one being leveled at Luther here. Religious delinquency (an actual charge) was not taken lightly; all universities were, in effect, state-funded Christian universities, and you only got to stick around if you (a) met a particular standard of social behavior or (b) brought in lots of money. A famous lecturer could get away with some eccentricities, but a pissant grad student like Luther would do better to color inside the lines.

Page 94: A somewhere different version of this complex and courtyard exists somewhere in  England (no apple orchard, though). The architecture is fairly contemporary to Luther’s time; new construction always means a University is doing pretty decently for itself.

England (no apple orchard, though). The architecture is fairly contemporary to Luther’s time; new construction always means a University is doing pretty decently for itself.

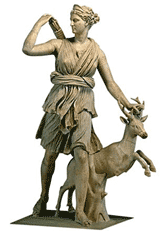

The bronze statue in the middle, being sketched by an admirer, is a copy of a much-copied classical statue. It’s Artemis, virginal goddess of the Hunt, hauling her bow around and petting the head of a wee stag. I’m pathologically fond of Greek mythology, so buckle down for a lot more of this nonsense as I wedge it into the story through any means possible.

Page 95: And now, for a rant on formal French gardens: my arch-nemesis. If you’ve ever taken a course on the Enlightenment, you will probably have written a two-paragraph essay on how the meticulously maintained parterre topiaries and geometrical patterns of the classical garden reflect the optimism of the era and the belief that man was drawing ever closer to touching upon Pure Reason and subjugating Mad Dame Nature. If you could keep the shrubs in check, truly, you were mere  steps from being master of your own destiny!

steps from being master of your own destiny!

France was the epicenter for this tidy brand of gardening (although they got the idea from the Italians) and if you go there today there’s still plenty of it about.

When Romanticism hit, the English struck back by getting into big rambling gardens full of gnarled willows and meandering paths, mysterious temples, wild brooks, etc. Amusingly, these “natural†gardens were constructed and landscaped just as meticulously as the formal gardens. Stonemasons did a brisk business throwing together fake ruins for awhile there. Regardless of the pretense of the English school, I do prefer gardens in which I actually have the opportunity to totally ruin my clothes.

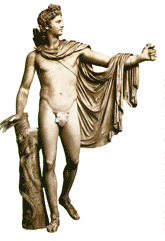

The statues here are marble. On the left is a standard statue of Apollo, the god of reason and

order and enlightenment and file folders and well-tuned string instruments and six-pack abdominals – and, incidentally, the twin brother of Artemis.

order and enlightenment and file folders and well-tuned string instruments and six-pack abdominals – and, incidentally, the twin brother of Artemis.

On the right are the twins (there may be a theme here) Castor and Polydeuces, aka the Dioscuri. Brothers to Helen of Troy, they were hatched from the same batch of eggs that resulted when Zeus (in the form of a presumably very sexy swan) mated with Leda. In some traditions, Pollux was born immortal; Castor, mortal.This drove them totally crazy, so they struck a deal with Zeus where they time-shared their immortality, keeping an apartment in Olympus and a condo in Hades. Nice work if you can get it.

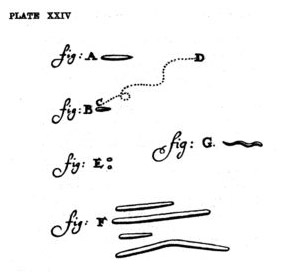

Page 96: Reader-type folks have brought up the interesting point that “infection†might not have been understood in the same way we medically understand it today. By the 18th century there had already been a fair amount of suspicion that small organisms could enter the body  system and cause disease; in the mid-17th century, Dutch microscopy pioneer Antony von Leeuwenhoek did a fabulous experiment where he put some dental plaque under the lens and witnessed a lot of very excited bacteria (shown at right). Oh, and by the way, he had Baruch Spinoza’s lenswork recommended to him by a friend.

system and cause disease; in the mid-17th century, Dutch microscopy pioneer Antony von Leeuwenhoek did a fabulous experiment where he put some dental plaque under the lens and witnessed a lot of very excited bacteria (shown at right). Oh, and by the way, he had Baruch Spinoza’s lenswork recommended to him by a friend.

At any rate, evacuations, quarantines, and other countermeasures during the various plagues also demonstrated that people understood disease could be contracted from others – and it was already in use as an emotional metaphor. In Shakespeare’s play The Tempest, written early in the 17th century, Prospero watches his daughter Miranda go absolutely googly over Prince Ferdinand, and mutters:

“Poor worm, thou art infected!â€

And of course there was plenty of syphilis going around to cement “infection†as popular metaphor. So Luther’s actually cleaning it up, here. This is my very long winded way of saying: haha, suck it, readers! I was right!

Page 97: Sixteen was not an unusual age to start University, if you were a bright boy looking to go into a law, medicine, clergy, or academia in any serious way.

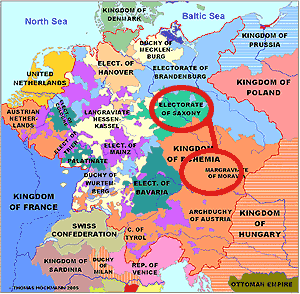

Nolte’s exaggerating when he says that they’re “halfway to the Uralsâ€. The distance between the University of Familienwald and the Western Urals is about the same as it is from LA to Chicago.  But still: this is not the cafe district in Berlin. This is well into the modern day Czech Republic, straddling Bohemia and Moravia. While the majority of the University’s inhabitants are Germans, the general population would be largely ethnic Slavs. Luther’s going to have a tricky time buying milk in town without a phrase book.

But still: this is not the cafe district in Berlin. This is well into the modern day Czech Republic, straddling Bohemia and Moravia. While the majority of the University’s inhabitants are Germans, the general population would be largely ethnic Slavs. Luther’s going to have a tricky time buying milk in town without a phrase book.

Page 98: As Nolte suggests, the University served a number of purposes for the State – a role that was rapidly changing as commerce, meritocracy, and ease of distributing writing transformed a formerly quasi-religious and very nepotistic institution into something much more closely resembling the secular research universities of today.

The University was becoming a factory for professionals as well as a focus for attention and prestige itself. University employees were suddenly being asked to be less “personal” in approaching their research, but also more publicly engaging. This still drives plenty of academics nuts, as they’re tugged between the poles of being a charismatic teacher, and being a good objective scholar.

The Prince appears to be more interested in the nuts and bolts than in having flambuoyant professors to brag about. You can guess which end of the spectrum Nolte thinks is more fun.

Page 99: Really that date should be in Roman numerals, but this is an underground student publication, so I can pretend they’re just being edgy.

Anyway, voila, the sacristy/catalog room!

Since it might not come up: Ariana is good at her job, because she innovates. She has something approaching a card catalog growing in the old vestment drawers. The first record of a formal card catalog isn’t until a government card catalog in 1789 in France; manuscript information was written on the backs of playing cards, which were then hole-punched and bunched together on a string. The information was taken in part because the foundering government could then identify the fancy books and sell them off to recoup revenue. Classy.

The chair by the fire is actually a musician’s chair, which you can visit in the European Decorated Arts section of the Art Institute of Chicago.