Notes for Pages 210-219.

<Â 200-209 |Â Notes Index | 220 – 229 >

210. You will recognize Panel 2 from alllll the way back here, maybe? There will be a quiz later.

211. There’s a great rundown on the whole rigmarole that formed a lady’s wardrobe over at The Macaronis. Whenever I leave the house in a t-shirt and yoga pants, I give silent thanks for being born now instead of then. Also when I get vaccinations and antibiotics.

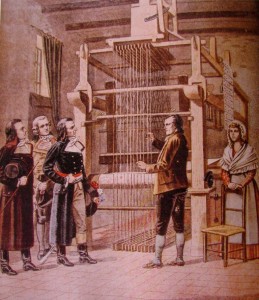

Clothing manufacture was quite a different thing in the 18th century than it is now. Much of the underclass in the largest city in the world at the time, London –  were employed in aspects of weaving. This included men, women and children. Virtually every aspect of the work was tedious and back-breaking and poorly paid, powered entirely by the human body, but that didn’t stop people by the thousands from trying to find work in the  field. Manual looms would shunt into a worker’s abdomen constantly during an 18-hour shift, causing internal wounds and disorders. Further into the century, technical innovations began to make it possible for an individual weaver to produce the same amount of work as several weavers (although the process was still entirely man-powered), and by the end of the century a fellow named Jacquard invented a true mechanical loom whichstarted to replace a lot of the manual labor. This posed a problem for the masses of people previously employed in weaving, but it did ultimately reduce the total amount of human misery concentrated in the industry.

field. Manual looms would shunt into a worker’s abdomen constantly during an 18-hour shift, causing internal wounds and disorders. Further into the century, technical innovations began to make it possible for an individual weaver to produce the same amount of work as several weavers (although the process was still entirely man-powered), and by the end of the century a fellow named Jacquard invented a true mechanical loom whichstarted to replace a lot of the manual labor. This posed a problem for the masses of people previously employed in weaving, but it did ultimately reduce the total amount of human misery concentrated in the industry.

For all that so much of the population was dedicated to making fabric and clothing, actually purchasing that clothing could be breathtakingly expensive proposition for the working classes. Often the workers – especially the small children – would be dressed in little more than rags. One of the stipulations of taking an apprentice, as many weavers did, was that the tradesman had to supply his new charge with a suit of clothes, although this requirement was regularly ignored. Runaway servants and apprentices of the era were often prosecuted, not for running away, but for “stealing†the clothes they were wearing.

Most of us know plenty about the horrors and glories of Victorian London (or think we do), but the 18th century was the real turning point between medieval society and modern, and paved the road both for the mechanical improvements of the 19th century and the social ones. Much of what happened in London then is relevant to the development of other Western cities as well. An excellent (and grim) read on the subject is M. Dorothy George’s classic book London Life in the Eighteenth Century.

213. Some folks have asked me about the painting that’s on the Rector’s wall in that central panel. I’ll be straight with you: I made it up. Looking  back at it, let’s say that it’s a take on the encounter between Christ and the Canaanite woman. This is a great moment from Matthew 15, one of the few times in the Bible where a female character resoundingly wins an argument.

back at it, let’s say that it’s a take on the encounter between Christ and the Canaanite woman. This is a great moment from Matthew 15, one of the few times in the Bible where a female character resoundingly wins an argument.

While Jesus is visiting Tyre, a Canaanite (non-Jewish) woman starts following him and his disciples, begging Jesus to cure her daughter of demon possession. Jesus ignores her but doesn’t tell her to buzz off, and his disciples start to bitch about it and ask him to get rid of her. Finally Jesus tells the woman that “It is not right to take the children’s bread and toss it to the dogs” (translation: Sorry, pagan lady, I’m just here for the Jewish folks).

The woman replies, “Yes, Lord, but even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their masters’ table.”

Whereupon Jesus, suitably impressed, congratulates her on her faith and tells her to go home to her daughter, who is cured.

So yeah. Let’s say that’s what the painting is of. It’s a nice excuse.

214. And here is where I remind you that this comic is not appropriate for the under-18 set! Let’s talk about 18th century birth control, why don’t

we. Condoms didn’t really come into their own (so to speak) until the 19th century, when the industrial use of rubber

allowed for mass production of reliable product; there were some sporadic mentions of sheaths dating back to the 16th century, but they were mostly made of stuff like linen and silk and were designed to reduce the spread of disease.

By the 1770’s there are records of condoms made of sheep and goat guts – reusable, apparently! Boswell, the Marquis de Sade and Casanova allmention using condoms, but again mostly as a means of avoiding whorehouse syphilis. (Delightfully, Casanova refers to the condom an “English raincoat.”) In short, condoms were not a wide-spread solution.

So what does that leave you with? A lot of working class women apparently relied on extended breastfeeding to reduce their fertility, hiring themselves out as wet nurses. If a woman had already detected a pregnancy, there were plenty of orally-taken abortifacients on the market – ranging from harmless folk-magic to genuinely poisonous substances. There were also plenty of (blood-curdling) methods for physically inducing a miscarriage, none of which would’ve been a woman’s first choice. Anecdotal evidence mostly suggests that the withdrawal method – coitus interruptus – was the most popular solution. And it was understood that the only time you could safely have sex without risk of getting a woman pregnant was during the nine month interval where’d you already gotten her pregnant.

At any rate, our leads here seem to be avoiding the issue entirely. (Again, so to speak.)

215. I got some interesting responses to these boudoir scenes! I think the most intriguing is the assumption that people in the 18th century were just as repressed about sex as bourgeois Victorians were, and that a relationship like this would be a radical departure from social norms. Not so, friends. It’s unusual for Ariana to have removed herself from the marriage track, and on the whole, the professional and upper classes of male were engaging in a lot more non-marital sex than the women of their class, but sex in 18th century Europe was just as accepted and inevitable an element of adult life as it always has been.

So Luther’s choice of girlfriend is unusual, but it’d be a lot more unusual if he were a virgin. And Ariana, having been raised in a University town full of randy youths and egomaniac males, has been exposed to an atmosphere of hanky-panky from a much earlier age than her Pietist boyfriend. I also just find it fun to reverse the expectation of historical fiction that “women of quality” will be doe-eyed gasping innocents or jaded whores, and that men will be knowing Lotharios or white knights.

I have a short story about Ariana’s romantic history (and how she came to be both so casual and so secretive about liaisons) that will wind up in a collection at some point. It was originally going to be a monologue for this scene, but it didn’t quite jive.

If you’ve been tracking the panels showing the moon, you can get a sense for the span of time that this compound scene covers.

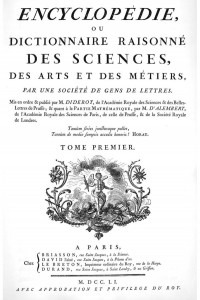

216. Encyclopedia. Have I talked about this before? If I have, I apologize, but it’s kind of worth reiterating. One of the grandest intellectual projects of the Enlightenment was the Encyclopédie, heroically edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert. It was inspired by an admirable,  earlier English attempt at creating a comprehensive reference on science and craft, the two volume Cyclopedia, published in 1728. Its creator intended a much more ambitious work, but was unable to complete the project. Ultimately Diderot and d’Alembert ended up helming what was originally going to be a licensed French translation of the work, but turned into something much grander, an immense, elaborately illustrated project that spanned 28 volumes in 14 years and involved over two dozen contributors (including Voltaire and our friend Rousseau).

the Encyclopédie, heroically edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert. It was inspired by an admirable,  earlier English attempt at creating a comprehensive reference on science and craft, the two volume Cyclopedia, published in 1728. Its creator intended a much more ambitious work, but was unable to complete the project. Ultimately Diderot and d’Alembert ended up helming what was originally going to be a licensed French translation of the work, but turned into something much grander, an immense, elaborately illustrated project that spanned 28 volumes in 14 years and involved over two dozen contributors (including Voltaire and our friend Rousseau).

The Encyclopedie represented a lot of new thinking, from its precise and fussy organization of the material (the “Figurative System of Human Knowledge” that appears in it  is an inspiring early infographic) to content that occasionally ruffled the feathers of both Church and state authorities.

“Instructional plates” – the term “plates” for an illustrated page is a technical printing term. Text-only pages would be typeset in movable metal type slugs, each letter or symbol picked out of a tray and arranged to form the content, inked and then pressed onto the paper. Illustrations would be engraved separately on large metal plates, sometimes pressed on different kinds of paper depending on the requirements of the ink.

218. This page took me awhile. Thanks are due, as usual, to anonymous, church-climbing tourists to the Czech Republic and Germany for posting their high-resolution photos of well-preserved towns. You can see Familienwald’s (not yet named) river in the distance; it’s probably a tributary of the Morava, and it feeds the lake that the bachelor party took advantage of. The river is part of why Familienwald has been a human habitation for so long. More on that later, as always.

219. We’ve seen the broken watch before, if you’ll remember. Grad students are free to surmise that this is an authorial comment on the brief segment of intimate calm these last few scenes represent in the story.